Just before the pandemic, as part of my quest to find out about my family which came from China, I travelled to Shanghai. This is the story about how in my search for a connection, I found The Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum.

The museum is a touching testament to an era, a place, and a community of peoples helping each other, and I recommend that anyone, everyone, even without a connection, visit. It is very profound.

So far, its interesting; and perhaps even more interesting as the story unfolds.

As I said, the museum was such a heartfelt place, so many stories told, so many lives portrayed; I felt that it had been created by someone very special, with a unique feeling and generous soul. My experience stayed with me, giving me comfort throughout the isolation years.

And then: a few weeks ago I was in Umea, a tiny university town in Sweden’s Arctic Circle, for the annual conference on sustainability and gastronomy, whose organizer is Edouard Cointreau, of Hallbars.com and Gourmand Book Awards, among his many other projects, such as the Beijing Bookfair, and the Paris Village International de Gastronomie (this year taking place 7-10 September—meet me there?).

Edouard was the first (and so far, only) reader of my entire memoir manuscript ; it was a huge job, he read every chapter, even my most embarassing ones; I will always be grateful for his thoughts, editing, ideas and encouragement—well, really, for everything. He was especially touched by my visit to the Shanghai museum; China has been his home for many years, with family, friends, and a creative life there.

So there we were in The Arctic Circle, a buzzing gathering of food writers, chefs, cookbook authors, gathered from all over the world, kibbitzing and shmoozing, hearing each others stories and presentations in this summer world of near-24 hour sunshine which was disorienting but also exhilarating. We watched and gave presentations, sampled indigenous foods and drinks, and in general enjoyed the atmosphere and interchange of ideas.

Anyhow, you never know who is going to show up at these gatherings—it can be mind boggling and wonderful. Suddenly, Edouard came running up to me.

“Someone from the Shanghai Museum is here! He is an old friend of mine, Xu Long, one of China’s 2 or 3 most famous chefs, and his close friend (also a chef) was the founder of the museum. I knew about the museum from reading your manuscript and immediatly told him about you being in Umea.

I guess I hadn’t thought that the founder of the museum would be a chef, and what a chef. Besides his fame in his own right, he is a disciple of Chef Du, of whom I am a great fan—a lovely guy with a great palate and food sensibility. Chef Du is one of a handful of chefs whose face is on a postal stamp.

Nor did I, to be honest, think the founder of the museum would be Chinese. I thought that it was a role which perhaps a Jewish organization would take on. But Chef Xu Long is very interested in Jewish culture as is his friend, the museum’s founder.

And, as they are taking the museum on tour to the USA, they want to reach out to those interested. Perhaps Edouard knew of someone?

That was when Edouard tugged at my arm in a gathering of chatting chefs and foodwriters: “One of the people involved in the Shanghai Jewish Museum—his friend and colleague was its founder—is HERE.” I stood there slightly dumbfounded for a moment, wondering what was going on, why would he be at a gastronomic conference….when Edouard continued: “He is a chef”.

And that was how both Edouard and I learned the behind the scenes story of the museum, how it was created with affection and respect (which was obvious to me as a visitor). Mr Xu Long described to us his friends involved in the project, and his interest in the Jewish culture and in particular this time and place that both International Jews and Chinese shared. Mr. Xu Long’s personal hobby is collecting coins from Israel, and sat us down, opening a book that displayed his collection, and the time eras they came from, the history of the land they told.

Then he opened a second book and showed us photographs of the museum and exhibits from the museum, narrating all through. He asked if I had any memorabilia from my grandmother which, alas, I don’t.

I can’t even imagine how this museum was crafted from a vision, put together with great care (and affection) and I would urge anyone going to Shanghai to put the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum high on their list of places to visit; it is a testament to human spirit even in darkest of times. It may well make you love humanity a little bit more, in case, like me, your spirits have been lagging.

For me, my trip to Shanghai had nothing to do with the usual sightseeing: it was, in fact, a special pilgrimage: something I had wanted to do all of my life. Here is why: My father’s father, my grandfather, Papa, was married to Mrs Gordon (who we always called Mrs Gordon, everyone we knew did. ). She and Papa had both been married before; Mrs Gordon was now my grandmother.

We might not have been blood related, but we had a special bond; I don’t even remember if she spoke English. Mrs Gordon was often unwell and spent much of her time resting on the couch; when she saw me enter their apartment then patted on the cushion next to her, and I ran, hopped on, and joined her. They lived on Turk Street in what came before the Western Addition, at the time called: McAllister Street. It was basically a small shtetl transplanted to San Francisco, with delis redolent of pickle barrels, bookshops that sold holy books and ritual items, shops full of used furniture and junk, and my favourite: the Ukraine Bakery, where we bought poppyseed studded Kaiser rolls, the air smelled heavenly of baked goods, and where flour-dusted women would grab me and kiss me, pinch my cheeks and stuff cookies into my hands and pockets when I went out and about with Papa.

Returning to the apartment with bags of goodies for lunch, as we opened the door, her face always lit up. I ran to her, leaning in as she hugged me. We didn't need to speak English, I could tell that she loved being near me and I felt the same way towards her. Meanwhile, Papa was busy slicing kosher salami and making sandwiches.

That whole generation, my grandparents generation, of American Jews were mostly European; they fled terrible things; they spoke Yiddish. They were wonderful bakers and cooks. But what made THIS GRANDMA different from the other European Jews of that generation, was: she didn't come from Europe. At least, not directly. She came from China—Harbin, to be exact, later Shanghai. San Francisco had a large population of Jews from China when I was a child.

Was she originally from Russia? Ukraine? Poland? It was Eastern Europe, but beyond that I never knew. Had she come to Harbin as a child or young bride? Her first husband, Wolf Gordon, had been an import/export businessman; Russians had built much of Harbin; the Gordons were active in the Harbin Jewish community.

Harbin had been an amazing place to be Jewish, with a vibrant cultural life in an International community at the heart of Chinese life. When things changed--war and tumult-- most fled south to Shanghai, where there was already a huge Jewish and European community to welcome them and help them get settled.

In my grandparents' little San Francisco apartment (which had the scariest, most rickety elevator imaginable; it was tiny, had no outside door (only a grate) and it got stuck a lot), I gazed at her beautiful hand painted cups and saucers, tea pots; such delicate lines painted onto the cups, often they told a story: a little vignette drawn right on the cup; I spent so much time, drawn into the stories I saw in the paintings on the thin, nearly translucent ceramics. I still remember the nuances of color, the delicate and diverse brush-strokes. On the shelves too were incense burners (mysterious to me), shiny and glittering fabrics, and a samovar that was never cold. We children (my brother and I) developed a close feeling towards our San Francisco family and its tiny China outpost. It was there, with that side of the family, that we felt special, and appreciated.

But life, as it goes, takes away an era, and those you love with it. You grow up, you don’t know who to ask questions of, or they don’t want to talk about the past, or they are simply no longer here.

So, I never pursued tracking anything down from that time and place, until the year 2019, when the Gourmand Cookbook Fair and Awards were to be held in Macao, China. My husband Alan said to me: "THIS year, you go to Shanghai! You shouldn't keep putting it off, who knows what the future brings?" (We hadn't even imagined a pandemic). "Just take a few days, and see if you can find any fragments of your grandmother's life, you've always wanted to do it". He had been with me in Beijing and was hugely touched by our tracing my late brother's life there and how comforting that had been.

I wasn't eager though; to be honest, it seemed frivolous and far fetched. How would I find a remnant of her life when I had so few clues as to where to start? Why spend substantial money on something that seemed so impossible, so selfish even. And I was afraid. Afraid of failure and coming up empty-handed.

A long flight to a city where I had never been wasn’t appealing either. And... and... and... I could give you a long list of reasons why it didn't seem attractive. But really: I think I was just afraid.

Alan encouraged me, that even if I found no remnants of my grandmothers life or the community, it was enough--a lifelong dream in fact--to try.

After Shanghai I planned to fly to Macao for the Gourmand Awards and Bookfair—where I would do onstage cooking demonstrations. So, even if I left Shanghai without knowing more of my grandmother's past, at least I would know I tried—I could relax and enjoy the Gourmand Cookbook Fair and Macao.

So, I checked into my hotel in Shanghai, and as I do in most places, brewed a pot of tea, relaxed and perched next to a window to unwind from the flight. Here, I watched neighbourhood life: residential enclave to my right, a commercial street to my left, and looking down across the little park, I saw what looked like a restaurant. I already felt like part of the hood.

As darkness fell, places closed; I was now hungry and set out by foot to explore. The neighborhood, though, no longer felt cohesive. Still, I managed to find a convenience store—and oh wow wow wow, I had forgotten how great convenience stores are in Asia. I bought a big fat steamed green onion bun, a hard cooked egg, a sachet of pickled mustard tuber which is one of my favourite China treats, along with a bottle of Tsintao beer, all to enjoy back in my hotel room, at the window, watching the nighttime neighbourhood. Then I went to sleep happy.

Next morning, in the daylight, it was a different place again: bustling, building, selling and buying, streets and alleyways teeming with...everything. Bicycles were everywhere.

Clothing was drying on a rack set out on the pavement and on the corner, a girl hula-hooped with great determination. Directly behind the hotel and around the corner was a street lined with breakfast foods; inbetween several of the stalls I saw an open door. It had a sign which I couldn’t read, so I walked in and found myself in a huge indoor wet market, full of vegetables, fish, meats, so fresh and so clean. I was thrilled.

I stopped at most vendors and admired the vegetables, dried goods, the fish and the meat; the vendors in turn were amused at me.

I looked so out of place I might have been dropped right in the market by a rocket ship, but instead of being treated with suspicion, I felt affection, if a bit of confusion as well (this was not a tourist area; I think it might have been a garment district.). No one at all spoke English. I was all alone, and yet: everyone went out of their way to help me along.

When I had been planning my trip, I researched how to find any tidbit of information, even the merest crumb, that might lead me to my grandmother and the community she came from; it was, after all, my own heritage too. I looked into walking tours of “Jewish Shanghai” but none were held the right time or day, so I continued to look online. That’s when I discovered the Jewish Refugee Museum.

It seemed a good place to start; I didn't have a lot more to go on. I had no idea if she had spent much time in Shanghai, or if she had only stopped there briefly en route from Harbin to San Francisco. I had yearned to know more for so long, it was time.

Here is what I did know: In the early 20th century many Russian Jews fleeing pogroms in Russia settled in northeast China (formerly Manchuria), especially The city of Harbin, playing a key role in the shaping of local politics, economy and international trade. Life in Harbin, especially cultural, community life, was wonderful for the Jews.

But in the early 1930s, Japanese occupation sent most to Shanghai where they created a community that would later welcome Jews fleeing the Holocaust. Shanghai was an important safe-haven for Jewish refugees since it was one of the few places in the world where one didn't need a visa. Ships from “Europe” brought the fleeing remnants of European Jewry, seeking safety to the International enclave. Not all the ships or its passengers made it, but by 1941, nearly 20,000 European Jews had found shelter there.

In 1943, Japanese occupying forces required the Jews to relocate to an area of 0.75 square miles in Shanghai's Hongkew district (today known as the Hongkou District) which became the Shanghai ghetto and is now the location of the museum and sign-posted walk I visited that day.

To be honest, I had worried that it would be disappointing; the trip had been was such a big deal in my own inner pilgrimage, and these things are hard to live up to. I told myself that it was enough that I had just gone there; anything I saw, or learned, even the smallest thing, would be enough. I was not prepared for the absolute tour de force that the museum is: an emotional, hand-crafted, heartfelt place that I felt hugely enriched by visiting. I would have felt this way even if I had no connection to the community.

Housed in one of the original synagogues, the museum is part of the old Shanghai Jewish Ghetto, surrounded by a guided/signposted walk through the area. At the entry gate, a young volunteer, who spoke perfect English offered to take me around as a guide. He told me of his warm feeling towards Jews from his university studies in America. He added: "Chinese people do not know much about Jews, so it is my pleasure to help in this way".

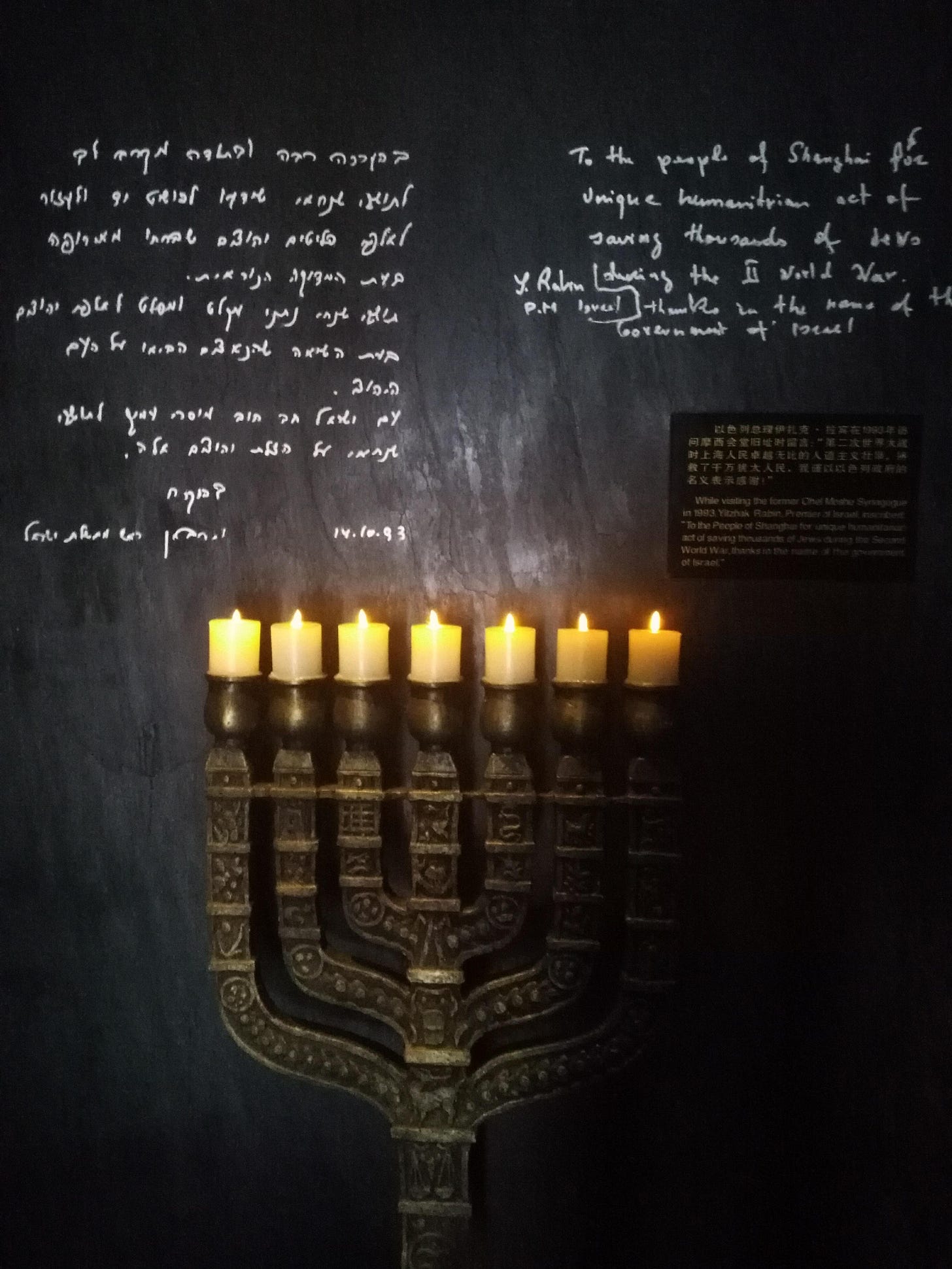

The museum is exceptional; it documents the huge vibrant community that once flourished. As WWII approached, the Japanese Army corralled the Jews into a small area to form a Ghetto. The museum documents the every day life of the Jews and the sheer generosity of local Chinese towards them: they didn't have much, and they shared what they had with these new refugees. Shanghai saved so many lives.

Shanghai saved Jewish lives when the rest of the world turned away. To me, that was enough. I was grateful for being allowed to follow in the footsteps of all who passed through this place, this life, knowing that at some time it had been my own grandmother.

Funnily enough, I am pretty sure I was the only Jewish person visiting that day, until later when I overheard a woman with a distinctly NYC accent. The exhibits were filled with Chinese people spending the day; lone visitors and whole families. One little girl loved my watch which is printed with big red tomatoes and kept pointing at it and giggling, in fact, she might have been giggling at me too; she was so adorable, bursting with her delight at life. She made me laugh so much; and try as I might to give her the watch, her parents would not let her keep it. Throughout the days visit, in and out of rooms and exhibitions, wherever I saw that little girl, we were like secret best friends, with so much laughing, smiling, and pointing at my tomato-watch, shared.

At the end of the visit, we passed a memorial wall carved with names. "You can have a look if you like", said my guide: "Maybe your grandmother's name is on it?"

What are the chances my grandmother's name would be on this wall? I thought. So many came through, so many lived there. By then, I was pleased to have been witness to the story told within the walls of the museum, that it wasn't even necessary to look for her name. Anyhow, it was so unlikely, since I had already read in the exhibit that since there was no room for everyone’s name on the wall, they had simply put up the names of the earlier members of the synagogue and community, the ones who paved the way for the later arrivals rescued from Europe.

But the guide had been so helpful, and he seemed hopeful himself about seeing the name on the wall, so eager to be part of the story that he often takes visitors through, that as a way of being appreciative, I thought: I will search for her name.

I casually glanced over to the wall, before even starting to search: there, right in front of my eyes, staring at me, was: My Grandmother. I was astounded; the little guide was in awe but unsurprised. He nodded sagely, as if he expected no less.

Along with my grandmother were the names of the 3 members of the Gordon family (her first husband and another name who I think was their daughter, my cousin Mattel, were together with her) on the wall. As a child, I had pieced together from various memories, and sometimes wondered: is any of this true? When i saw their names, even cousin Mattel who, if it is the same person, had a different name in China, she must have been born there? I felt almost breathless. It was the first, real, tangible, proof of our family mythology, what was real and not, the connections to China, and I, like my brother before me, felt an incredible bond, suddenly, to this place and culture.

For a moment, I nearly passed out; then, I burst into tears. Suddenly I was back in that little San Francisco apartment on Turk and McAllister Street, sitting with my grandmother, content to just be admired and loved, surrounded by all these bits and pieces of a life lived in China, that I really didn't know much about.

This was more than I had expected, more than I even considered. I thanked my guide, who gave me a map of a several block walk encompassing the original Ghetto, the area that surrounds the around the museum. The walk is designated "The Ark" because like the biblical Noah, Shanghai saved so many Jews from the flood of catastrophe. I followed the streets, noting the plaques and signs of who had lived there, narrating and commemorating what their lives had been like. I thought of a family friend’s childhood spent playing on the Shanghai Jewish Soccer team, another friends grandparents who owned a fashion shop. Some of the buildings still had Yiddish/Hebrew lettering carved into their facades, the streets now bustling with Chinese life.

The day was a glaringly hot, Shanghai summer day, and I meandered along the streets, turned the corners, past the buildings that had once been bustling with Jewish life. I bought a jian biang on the street-- that wonderful thin pancake spread with egg, and sauces, something crisp and crunchy, a handful of cilantro and green onions to top it all and then folded over and wrapped up; quintessential street food and oh, one of my absolute favorites.

I carried it to the park across the street, found a bench shaded by fragrant leafy tree, and started to nibble. The park was full but not crowded, with others enjoying the day; across from me I saw a touching memorial—in Mandarin, English, AND Hebrew, commemorating the Jewish community that had once lived there.

Back on the street I saw a building that once housed the Jewish theater, whose rooftop garden had offered socializing along with cooling breezes. I felt so calm; I felt like I had come home, been welcomed, borne witness, and could now leave and take it with me, and hold it forever in my heart. With my grandmother.

A few resources:

“Passage to Shanghai”, by Greg Patent (food writer, master baker, and newsletter author: “So You Want to Move to Maui”.). He was born and spent his first years in the International enclave with his Bagdadi parents and grandparents.

Also this video , sent to me from one of their dear friends, Dinah Stroe:

This film trailer, recommended by two friends of friends from Harbin then Shanghai:

And this:

The Museum:

If you can’t make it to Shanghai, but can come to New York, the museum is holding a Touring Exhibition. Here are the details— you are invited.

“Dear Guest:

It is our honour to invite you to the Opening Ceremony of “Shanghai, Homeland Once Upon a Time——Touring Exhibition in New York on Jewish Refugees and Shanghai”. We look forward to your presence.

Time and Date: 11:00 a.m., August 1st (Tuesday), 2023

Venue: Amphitheater (Liberty Street Entrance)

Fosun Plaza

28 Liberty Street, New York, NY, 10005, United States

Dress Code: Business Casual

Hosted by Shanghai People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries

Organized by Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum

Dara Horn's recent book on antisemitism, "People Love Dead Jews" devoted a chapter to Harbin and Shanghai. Arthur Rotstein, the then young Jewish-American documentary photographer, visited Shanghai in 1946 to photograph the Jewish refugees still awaiting resettlement to draw attention to their plight: https://arthurrothstein.org/portfolio/shanghai-jewish-refugees/

Marlena, once again, we dive into the warm broth of your words. This is where your recipes are, sharing your perfectly crafted gift for life.

Your stories, a bowl of global soup, warm my heart like no other master crafts person ever has.